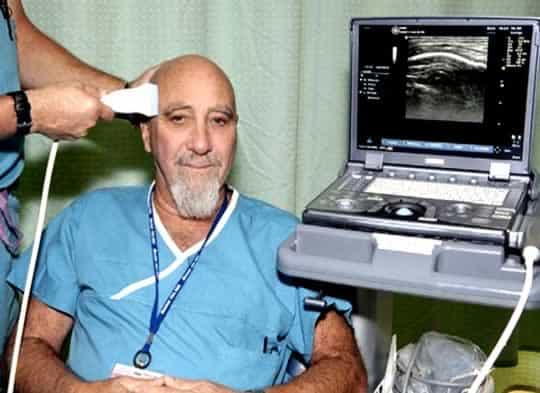

The unusual idea occurred to Dr. Stuart Hameroff (above) after he heard about ultrasound studies on the brains of mice.

Ultrasound equipment—which uses sound waves to see inside the body—is familiar to anyone with children as it’s used to check the health of an unborn child.

But what would it do, Dr Hameroff wondered, if he used the ultrasound machine on the human brain?

He suggested to his colleagues that they should try it on patients with chronic pain to see if it would help. His colleagues said he should try it on himself first.

So he did.

At first nothing happened, said Hameroff:

“I put it down and said, ‘well, that’s not going to work,’ and then about a minute later I started to feel like I’d had a martini.”

The feeling continued for a couple of hours.

But perhaps this was all placebo: he expected to feel different and so he did.

The only way to get solid evidence was to conduct a study where neither patients nor doctors knew whether the ultrasound machine was switched on or not, then look at the difference between groups.

The pilot study was conducted on 31 chronic pain patients (Hameroff et al., 2012). After having the ultrasound applied to their brains for just 15 seconds, they felt slightly less pain, but the main effect was an improvement in mood:

“Patients reported improvements in mood for up to 40 minutes following treatment with brain ultrasound, compared with no difference in mood when the machine was switched off.”

The exact mechanism for how ultrasound affects mood is still unknown, but:

“What we think is happening is that the ultrasound is making the neurons a little bit more likely to fire in the parts of the brain involved with mood,” thus stimulating the brain’s electrical activity and possibly leading to a change in how participants feel.”

Perhaps the research will lead to a device that can help people with mood disorders:

“The idea is that this device will be a wearable unit that non-invasively and safely interfaces with your brain using ultrasound to regulate neural activity.”

The pilot study is now being followed up in double-blind clinical trials on more patients and using doses of ultrasound up to 30 seconds. The results of this study are currently being analysed.

Brain Ultrasound: How Sound Waves Can Boost Mood

Post image for Brain Ultrasound: How Sound Waves Can Boost Mood

Pilot study finds mood of chronic pain patients is boosted by left-field use of ultrasound machine. Could it work for all of us?

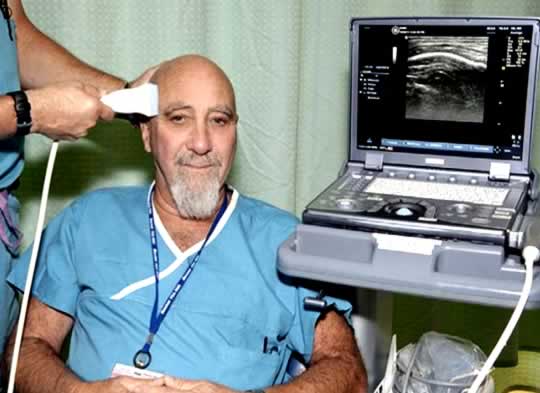

The unusual idea occurred to Dr. Stuart Hameroff (above) after he heard about ultrasound studies on the brains of mice.

Ultrasound equipment—which uses sound waves to see inside the body—is familiar to anyone with children as it’s used to check the health of an unborn child.

But what would it do, Dr Hameroff wondered, if he used the ultrasound machine on the human brain?

He suggested to his colleagues that they should try it on patients with chronic pain to see if it would help. His colleagues said he should try it on himself first.

So he did.

At first nothing happened, said Hameroff:

“I put it down and said, ‘well, that’s not going to work,’ and then about a minute later I started to feel like I’d had a martini.”

The feeling continued for a couple of hours.

But perhaps this was all placebo: he expected to feel different and so he did.

The only way to get solid evidence was to conduct a study where neither patients nor doctors knew whether the ultrasound machine was switched on or not, then look at the difference between groups.

The pilot study was conducted on 31 chronic pain patients (Hameroff et al., 2012). After having the ultrasound applied to their brains for just 15 seconds, they felt slightly less pain, but the main effect was an improvement in mood:

“Patients reported improvements in mood for up to 40 minutes following treatment with brain ultrasound, compared with no difference in mood when the machine was switched off.”

The exact mechanism for how ultrasound affects mood is still unknown, but:

“What we think is happening is that the ultrasound is making the neurons a little bit more likely to fire in the parts of the brain involved with mood,” thus stimulating the brain’s electrical activity and possibly leading to a change in how participants feel.”

Perhaps the research will lead to a device that can help people with mood disorders:

“The idea is that this device will be a wearable unit that non-invasively and safely interfaces with your brain using ultrasound to regulate neural activity.”

The pilot study is now being followed up in double-blind clinical trials on more patients and using doses of ultrasound up to 30 seconds. The results of this study are currently being analysed.